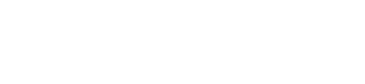

Lawyer's new book traces today's true-crime fascination to salacious 1800s murder trial

The case of Polly Bodine is the subject of Alex Hortis’ new book.

On a Saturday afternoon in April 1845, Mary “Polly” Bodine, after a three-week trial and more than two days of deliberations, was found guilty of murder by a Manhattan jury.

The gallows awaited.

But Polly was spared the hangman’s noose. Three months later, New York’s highest court (known then as the Supreme Court of Judicature) determined that she had been denied the right to a fair and impartial jury. The court found that extensive pretrial press coverage of the case, painting the accused in a negative light, had tainted those who sat in judgment.

The futility in choosing a panel for her retrial laid bare just how considerable the prejudging had been. After nearly three weeks, and the court’s examination of close to 4,000 prospective jurors, seating twelve unbiased citizens of Gotham remained elusive. The do-over proceeding had to be moved. It landed in Newburgh, New York, a town 60 miles north.

The case of Polly Bodine is the subject of Alex Hortis’ new book, The Witch of New York. But a whodunnit is only part of the story that Hortis, the associate university counsel at the University of Maryland Baltimore, sets out to tell. The book’s subtitle shares the rest: “The cursed birth of tabloid justice.”

The rise of media frenzy

For some in the media, all the world truly is a stage. Real-time coverage of trials has transformed courthouses into playhouses and their participants into unwitting actors. The curtain rises, and stories of human tragedy and misfortune are presented as dramatic entertainment.

The public also has developed a voracious appetite for tales of true crime. Topics include questioning the outcomes of past verdicts and playing detective to try to crack unsolved cases. A buffet of television shows, books and podcasts are available to satiate the hunger.

The origins of all this can be traced to a handful of long-ago cases, Hortis, 51, tells me in an interview. But Polly Bodine’s was the biggest and most important, he says.

But, as the author’s subtitle presages, a dark side exists. While purveyors of true crime “may claim they’re advancing justice,” Hortis says, “too often, their feeding frenzies obscure the truth and make actual justice more difficult.”

Freed from the constraints of an adversarial system, Hortis explains, producers have the ability to portray stories to correspond with their objectives. It takes “a lot of discipline,” he says, “for [them] to be balanced, and I am just not convinced that they can really do it.”

The Witch of New York is Hortis’ second literary effort. It follows his 2014 title, The Mob and the City: The Hidden History of How the Mafia Captured New York. That book had an “academic bent,” Hortis says, describing it to me.

The crime historian sought to write something for a broader audience. Looking for a subject, he happened upon Polly Bodine. To his amazement, despite the “true-crime craze” and significance of the case, he says “nobody had written a full-length, nonfiction history of it.” Not to mention, despite taking place ages ago, the case felt fresh and contemporary, Hortis adds. He recalls thinking: “Wow, I know this story.”

The date of the proceedings made Hortis’ work challenging. “I wasn’t sure it could even be researched,” the New York University School of Law graduate says. But “I was really lucky. There was such intense interest in the case that the newspapers had daily coverage of it.”

While Hortis was able to do much of his digging through internet resources, there was also a gumshoe component, including trips to various libraries and archives, where he found himself looking through boxes of newspapers that probably hadn’t been touched in close to 200 years.

Alex Hortis is the author of The Witch of New York. (Photo by Amy Jones)

Alex Hortis is the author of The Witch of New York. (Photo by Amy Jones)

The crime

On Christmas night in 1843, fire engulfed a home in Granite Village in Staten Island, New York. Inside were the burnt remains of 24-year-old Emeline Houseman and her toddler daughter, Ann Eliza. The mother and child had been bludgeoned, and it appeared the killer intentionally set the house on fire to cover up the crime.

Suspicion for the homicides quickly fell onto 33-year-old Polly Bodine, Emeline’s sister-in-law. Despite being from a well-to-do family, her motive, according to prosecutors, was to steal silver and jewelry from the home. Police soon arrested her and charged her with double murder.

The savagery of the crime and shock of the accused’s gender made the case irresistible for some of New York City’s newspapers. But they had still more reasons to salivate.

Bodine was separated from her husband and in a relationship with a man that was rumored to have led to several abortions. In fact, she was eight months pregnant at the time of her arrest, which would entice lurid coverage in the tabloids.

Moses Yale Beach of the Sun and the New York Herald’s James Gordon Bennett knew what had landed in their laps. The two men also detested each other and would let nothing, including journalistic ethics, stand in their way of scooping the other to sell papers. Fast sailboats and the use of carrier pigeons were employed to bring back news from Staten Island.

While Bodine had left her husband because he was a drunk, the Herald declared that “he was originally a man of considerable property and character, but after the marriage with this woman, (from her conduct as is alleged), became intemperate and debased.”

Bodine delivered a stillborn child while in custody, but the Sun reported falsely that she gave birth to a live child and smothered it in her jail cell.

With the Sun getting beat by the Herald more than Beach could stomach, he paid $100 for a supposed jailhouse confession from Bodine, assuring his readers that it was “authentic, and may be relied upon as correct.” It turned out to be nothing of the sort.

Hortis’ study of Bodine’s trials—three in all—also uncovered some shocking courtroom practices by today’s standards. Proceedings routinely went from early in the morning until late into the night, and New York courts had a custom of denying jurors food and water until they reached a verdict. “When I read that, I literally laughed out loud,” Hortis recalls.

Additionally, besides charging the jury on the law, it was not uncommon for judges of that era to share their opinions on the facts, what they believed they proved and even opine on the credibility of witnesses. Judge Amasa Parker, speaking to the jury at the close of Polly’s first trial—held in Staten Island and ending in a mistrial—offered that Polly’s “illicit intercourse [was] a fact for them to draw their own conclusions as to the depravity of mind that it had produced in that of the accused.”

The author concludes his superbly written and remarkably researched work by bringing the 181-year-old case to present day, writing that the Herald’s and Sun’s coverage, “portended our own tabloid justice,” pointing to “the lightning rush to judgment; the tainting of jury pools; the fracturing of America over social fault lines. The press put Polly on trial not only for the murder charge, but also for her unconventional life and sexuality. Before a minute of trial testimony, New Yorkers took sides on Polly’s guilt or innocence and projected their own worldviews on her case.”

All of this is Hortis’ way of saying that the public’s interest in true crime hasn’t changed since carrier pigeons were in the labor force.

Hortis achieved his goal of writing a book for a mainstream audience, but his wish list is not complete. “If I see somebody on the beach reading this book, that’ll make my day. No, that’ll make my year.”

Randy Maniloff is an attorney at White and Williams in Philadelphia and an adjunct professor at the Temple University Beasley School of Law. He runs the website CoverageOpinions.info.